This weekly post has everything you need for completing this week’s self-paced content and readings, plus an outline at the end for what’s covered during class meetings. This week is about contemplating the ethics and justifications for images of death in photojournalism.

This week there are more readings than usual, but no videos to watch.

Is photographing death justified?

We’ve previously discussed photojournalism ethics as they relate to the relationship between the photographer and people being photographed, but there are different ethical questions that come up about making and publishing photos of people who are dead or dying. Death is an unavoidable subject for anyone who seeks to document the world or hold the powerful accountable. But beliefs, rituals and emotions around death are both cultural and personal. Contemporary U.S. culture tends to be uncomfortable with death.

As you read this week’s readings, develop your own opinion on when it is justifiable to publish photos showing someone who is dead in the photo or dead by the time the photo is published.

Consider:

- Should someone’s death or dead body ever be shown in news media?

- What makes a death newsworthy?

- Where should news organizations draw the line about photos that are too disturbing or gory to publish regardless of the news value?

- What harm can come from publishing a photo showing death?

- What harm can come from not publishing photos showing death?

- Is news media more violent now than it was in the past?

Which Bodies Do We See?

This week’s reading was recommended in a previous week, so it will seem familiar if you read it then. This essay is about how U.S. news organizations frequently publish photos of dead people from other countries, but not Americans, and how this affects our perception of the world.

“When it’s common practice to publish photographs of war casualties from other countries but not to publish photographs of war casualties from the United States, then the very fact of visual access to the dead marks them as “other.” Likewise, if the refusal to publish images of dead American service members is a sign of respect, then the willingness to publish photographs of other people’s dead bodies can be read as a sign of disrespect.”

Some of the points made by the author came up in 2018 when The New York Times published a photo showing the bodies of men who had been killed in a terrorist attack in Nairobi, Kenya, as they worked on their laptops at a cafe. People were outraged — especially Kenyans — and pointed out that U.S. media never show victims of mass shootings in the U.S.

Two New York Times editors responded to explain their rationale:

Generally, we try to avoid identifying victims or showing unnecessary blood and gore, particularly if it is not central to the news story that the photograph accompanies.

But it is an important part of our role as journalists to document the impact of violence in the world, and if we avoid publishing these types of images, we contribute to obscuring the effects of violence and making debates over security and terrorism bloodless.

Many readers found this explanation unconvincing, for reasons summarized well in a response by George Ogola:

In the recent terrorist attacks in the US the New York Times has faithfully protected the dignity of victims. Their stories have not been told with any less clarity and profundity.

It is worth noting that photos published from the Columbine school shooting in 1999 do show bodies in aerial photos.

In 2009, the Associated Press published a photo of an injured Marine who later died, despite objections from the young man’s father and U.S. military leaders. The photographer, Julie Jacobson, said it was never a question of whether to take the photo, because that was her job and she’d taken photos of everything else that had happened. But photographers and editors always make decisions about which photos, out of thousands, get published and distributed. In a shared journal entry, Jacobson described her thought process:

“An image personalizes that death and makes people see what it really means to have young men die in combat. It may be shocking to see, and while I’m not trying to force anything down anyone’s throat, I think it is necessary for people to see the good, the bad and the ugly in order to reflect upon ourselves as human beings.

… We have no restrictions to shoot or publish casualties from opposition forces, or even civilian casualties. Are those people less human than American or other NATO soldiers?”

Review & Reflection

- What kinds of official policies have changed what photos we see?

- What kinds of unofficial policies or ethical norms have changed what photos we see?

- Do you think U.S. news media should treat deaths in the U.S. differently than deaths elsewhere?

- What are the arguments for and against showing U.S. military deaths?

- What are the arguments for and against showing victims of terrorist attacks?

The Risk of Not Seeing Death

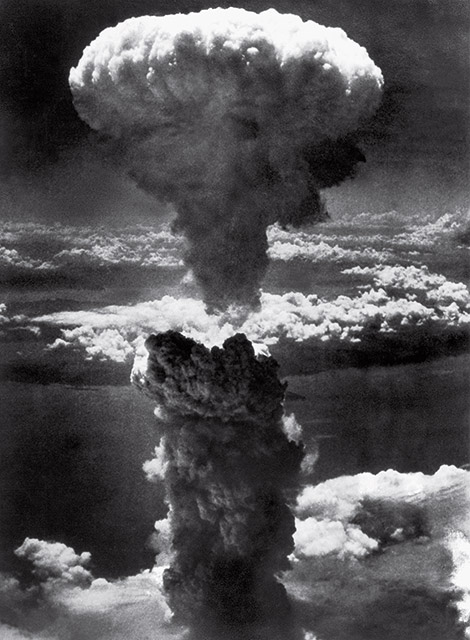

Many deaths are not documented, and many photographs showing death are not published. There is an argument that this “bloodless” representation of events prevents people from fully comprehending the impact of death. Most Americans are aware that the use of atomic bombs in 1945 against Japan caused widespread devastation, but many have only seen distant mushroom cloud photos. Only recently, with the internet and historic retrospectives, have photos from the ground become more accessible to people in the U.S.

This week’s reading about Emmett Till explains why his mother felt strongly about having an open casket at his funeral, despite horrific lynching injuries that made him unrecognizable. She also invited photographers to have the image more widely distributed. (The photo from Jet magazine can be viewed in this article with a click-through option.)

With mass shootings rarely photographed in the U.S., high school students started a #MyLastShot hashtag campaign saying they want photos shared if they were to die in a school shooting.

This week’s reading about Evelyn McHale personalizes the life behind the iconic photo. Although it is an old photo, it continues to have cultural relevance in part because there are very few public photos of suicide in the U.S. even though this is a leading cause of death among younger age groups.

Review & Reflection

- Do you think we should see more photos of death in the U.S.?

- If someone dies tragically, how do we react differently to memorial photos showing them alive vs. photos showing the death?

- Are photos necessary to understand the nature and impact of death?

- Are photos of death justifiable if they inspire people to take action or change their perspective?

Monday

• Preview of week’s materials

Wednesday

• No class – Veterans Day

Friday

• Photos at the moment of death

• Discussion about readings

• Review for quiz